‘Dead zone’ in the Gulf of Mexico has shrunk to about the size of Delaware

The “dead zone” in the Gulf of Mexico this year is much smaller than usual, measuring about 2,600 square miles, or a little larger than the size of the state of Delaware, says a Texas A&M University researcher just back from studying the region.

Steve DiMarco, professor of oceanography and one of the world’s leading experts on the dead zone, recently returned from surveying the area, from the central Texas coast to the Mississippi River delta of Louisiana. He and his research team found only several patches of hypoxia – oxygen-depleted water – in the gulf.

“The largest concentrations appear to be near Grand Isle, La., and then a little farther east to where the Mississippi flows directly into the Gulf of Mexico,” DiMarco says. “We were not expecting a large dead zone area this year, and the results appear to bear out those predictions. This is our fifth June cruise to estimate the size of the dead zone. We have seen a lot of variability in size and this year is our second smallest.”

During the past five summers, the dead zone has averaged about 5,000 square miles based on the annual survey by a group at the Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium (LUMCON). The June survey by DiMarco is done to provide an estimate of the dead zone’s variability over the course of the summer.

Hypoxia occurs when oxygen levels in seawater drop to dangerously low levels, and persistent hypoxia can potentially result in fish kills and harm marine life, thereby creating a “dead zone” in that particular area.

Such low levels of oxygen are believed to be caused by nutrient pollution from farm fertilizers and other land-based sources as they empty into rivers such as the Mississippi and eventually make their way into the Gulf. In summer, the size of the zone has been shown to be influenced by the nutrient runoff, volume of freshwater discharged and prevailing winds, which control the freshwater river plume’s movement.

The Mississippi is the largest river in the United States, draining 40 percent of the land area of the country. It also accounts for almost 90 percent of the freshwater runoff into the Gulf of Mexico.

DiMarco’s research on the dead zone is supported by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) Center for Sponsored Coastal Ocean Research, as part of its long-term commitment to advancing the science to inform management practices aimed at mitigating the hypoxic zone.

“Why it is a bit smaller could be a combination of several things – including lower nutrient loading and lower freshwater volumes from the Mississippi River or prevailing southerly winds across the continental shelf in June,” he explains.

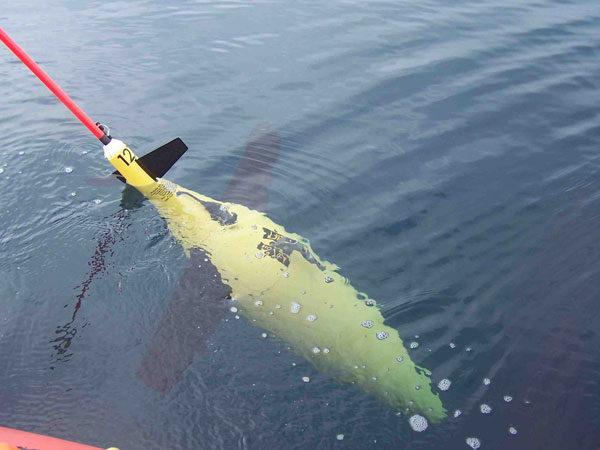

This year, DiMarco used new research tools called ocean gliders. The torpedo-shaped cylinders were placed in the Gulf and they transmit key information back to shore about ocean temperature and salinity, and most importantly, dissolved oxygen concentration of the seawater. Two of the gliders are now operating in the Gulf’s dead zone and furnishing key info by satellite about every six hours, DiMarco says.

The gliders are planned to be in the water until early September 2014. The glider data are made available to the public by the Gulf of Mexico Coastal Ocean Observing System (GCOOS) and the NOAA Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS). Both GCOOS and IOOS are providing funding for the glider aspects of this experiment.

#TAMUresearch