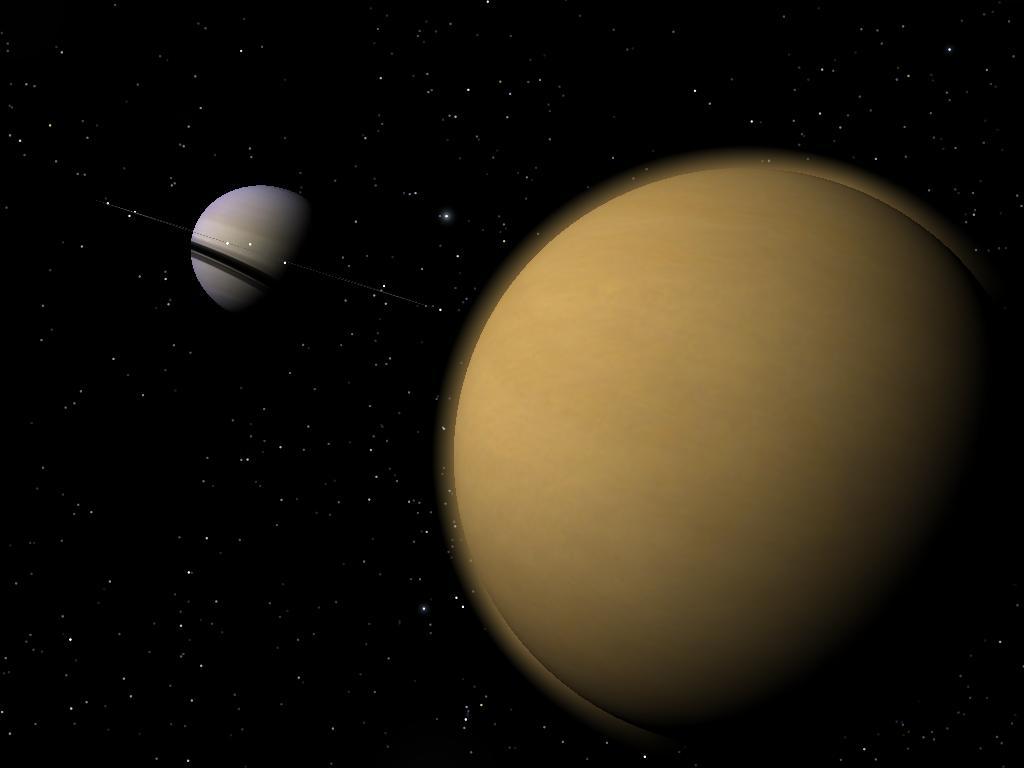

Sand dunes on Saturn’s moon Titan act much like those in Earth’s deserts

Image: Wikimedia Commons

A detailed study of Titan, Saturn’s largest moon and the second largest in the solar system, shows that its enormous sand dunes have been modified by long-term changes in wind conditions and may respond similarly to climate changes like Earth’s great sandy deserts, according to a study led by a Texas A&M University professor.

Ryan Ewing, assistant professor of geology and geophysics at Texas A&M, along with colleagues from Cornell University and the University of Paris-Diderot, have had their findings published in the current issue of Nature Geoscience.

The team used data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft to examine the landscape on Titan, specifically the sand dunes that cover large equatorial areas of that moon.

They found specific types of dunes that indicate that the winds shifted over long-time scales. The time scale needed to change some of the dunes exceeded 3,000 Saturn years (about 90,000 Earth years.)

“The time scale exceeds what we thought were the dominant dune forming wind cycles on Titan, and makes us think about winds changing in Titan’s past,” Ewing explains.

“It takes so long to shape and move the dunes because the dunes are enormous (many of them over 300 feet high). These dunes are on par with some of the largest here on Earth.”

Ewing adds that these timescales imply that Titan’s dune-covered landscapes may be changing as Saturn’s orbit changes over tens of thousands of years, “and this is somewhat similar to how some of Earth’s sandy deserts have evolved.”

Discovered in 1655 by a Dutch astronomer, Titan is about 50 percent larger than Earth’s moon and has a climate that is somewhat similar to Earth’s. It’s believed to have rivers, lakes and even oceans in parts of the moon, but has large deserts in other locations. It is the only known moon that has an atmosphere.

NASA’s Cassini spacecraft makes frequent fly-bys of Titan and its images show most of Titan appearing much drier than Earth. But in 2012, Cassini flew over Titan’s northern polar region and detected a river that is much larger than the Nile River on Earth. It also showed a large area of water that resembles our Dead Sea.

“In parts of the Sahara Desert, for example, some of the largest dunes are thought to have formed around 25,000 years ago and these dune patterns are still visible. Smaller dunes overprint the larger, older patterns. We see the same overprint of smaller patterns on larger ones on Titan,” Ewing notes.

In their next step, Ewing and his colleagues plan to use global climate models to explore possible wind conditions in Titan’s past that might have affected the dunes.

The project was funded by NASA’s Cassini Data Analysis Program.

News coverage: Scientific American

#TAMUresearch