By studying feeding habits, biologists can help protect largest of all fishes

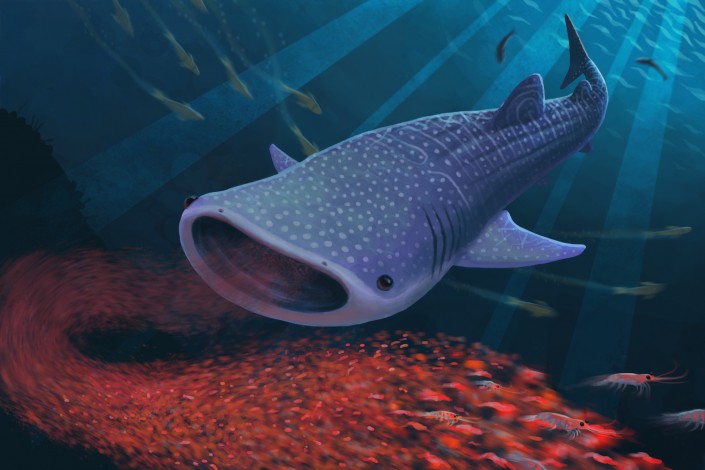

Illustration: Research Communications and Public Relations, Academic Affairs Communications

Whale sharks are the largest of all fishes, but their tremendous size can work against them when looking for food, which consists mainly of tiny krill and plankton. So to dive to great depths for a good meal, they have evolved cost-efficient modes of locomotion and diving that use as little energy as possible, according to a team of researchers that includes a Texas A&M University at Galveston marine expert.

Randall Davis, a marine biologist at Texas A&M with more than 38 years of experience studying marine life, and colleagues Mark Meekan at the Australian Institute of Marine Science and Lee Fuiman of the University of Texas Marine Science Institute, have had their work published in the current issue of Frontiers of Marine Science.

Learning more about their feeding and other habits could help protect these giants of the deep, Davis says.

Davis and the team attached small video and data recorders to two whale sharks near the Ningaloo Reef off the Western Australia coast, the second largest coral reef in the world behind only the Great Barrier Reef. These animal-borne instruments enabled them to track the three-dimensional movements of the sharks and study their locomotory performance while video recording their feeding behavior.

They learned that these enormous sharks are adept at minimizing the cost of swimming while pursuing prey at depth, often as deep as 1,500 feet. To save energy and improve foraging efficiency, the sharks used fixed, low-power swimming, constant low-speed swimming, frequent gliding at depth and asymmetrical diving, the team found.

“Whale sharks are mostly found in warm waters, but to get the food they need, they must dive to great depths, where the water is often 40 degrees or so,” Davis explains.

“Their behavior has evolved to conserve their energy as much as possible. Since they are so large and their food source is so small, they must stay down for long periods. The efficient use of energy at depth can mean the difference between locating sufficient food or going hungry.”

The team estimates that the swimming and diving behavior used by the whale sharks increases foraging efficiency by as much as 32 percent.

“Conservation of heat and energy while they are diving for food in cold waters appears to be the key for survival for these large creatures,” Davis adds.

Whale sharks can be 65 feet long and weigh as much as 75,000 pounds. They are the largest of all fish and were so-named because fishermen thought their great size resembled that of a whale.

Despite their large size, their diet consists of some of the smallest of sea creatures (whale sharks have no teeth) and they have a filtration system that can allow 1,500 gallons of water per hour to flow through their gills to capture tiny plankton and krill.

Though they have a menacing appearance, whale sharks are considered docile and unusually friendly, and divers have been known to catch a ride on their long tails.

“Because they are not aggressive, swimming with the whale sharks is a popular attraction at several sites in Australia,” Davis adds.

It’s believed the big fish can live 75 years or more, but their numbers are decreasing.

“The species is considered vulnerable by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), but fishermen in some countries, especially around Southeast Asia and Indonesia, continue to hunt them,” Davis says.

“Our research and that of other scientists may provide new information on their natural history that will assist with their conservation and draw public attention to protect these fascinating sharks from fishing.”