Hearing for early human ancestors similar to chimpanzees, data suggest

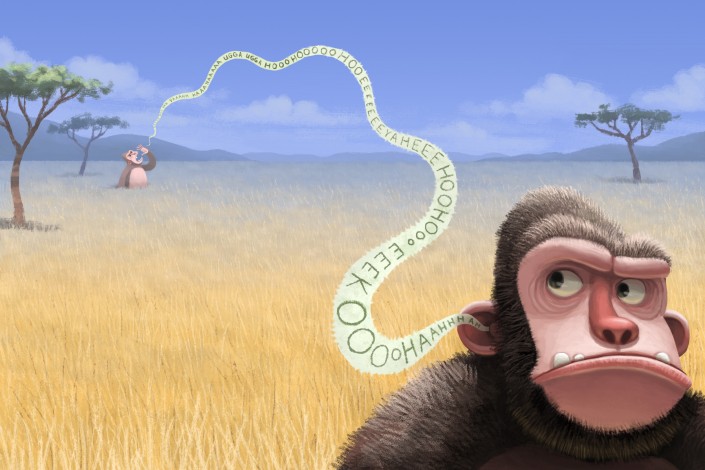

Image: Academic Affairs Communications/Research Communications and Public Relations

How well did some of the earliest human ancestors hear? Very well, and their hearing was more like that of a chimpanzee, according to a team of international scientists that includes a Texas A&M University researcher who examined the hearing capabilities based on studies of ancient skeletons.

Darryl de Ruiter, professor of anthropology at Texas A&M, and colleagues from Spain, Italy, South Africa and Binghamton University in New York have had their work published in the current issue of Science Advances.

The team looked at virtual reconstructions and X-ray (CAT scans) of the inner ear, alongside the tiny bones of the middle ear, of several skeletons found near the sites of Sterkfontein and Swartkrans in South Africa, where many of the earliest human remains have been discovered. The skeletons are thought to be about two million years old.

They found that the hearing ability of early hominins was more similar to that of a chimpanzee, and they likely were hearing higher-pitched sounds on a slightly different frequency than humans do today.

“The results show that these early hominins had a different hearing range, one that is more closely identified with chimps than humans,” de Ruiter explains.

“It’s likely that these hominins communicated vocally with each other, just as other creatures do today, though it is unlikely that we are looking at anything as complex as spoken language. Their hearing range was more chimp-like.”

It’s possible, team members agree, that this different hearing range and frequency was the result of the hominins trying to communicate over long distances.

“We know that they lived in the vicinity of grassy areas called savannahs,” de Ruiter adds.

“It’s likely they had to communicate farther than similar hominins who lived in a rainforest, where sound does not dissipate so quickly.”

The results show that hearing abilities have changed over time, the team concludes.

“We know that the hearing patterns, or audiograms, in chimpanzees and humans are distinct because their hearing abilities have been measured in the laboratory in living subjects,” the researchers note in a joint statement.

“So we were interested in finding out when this human-like hearing pattern first emerged during our evolutionary history. We know they communicated with each other, but they did not have the capacity for language.”