Keeping young offenders close to home results in fewer re-arrests

Infographic: Texas A&M University

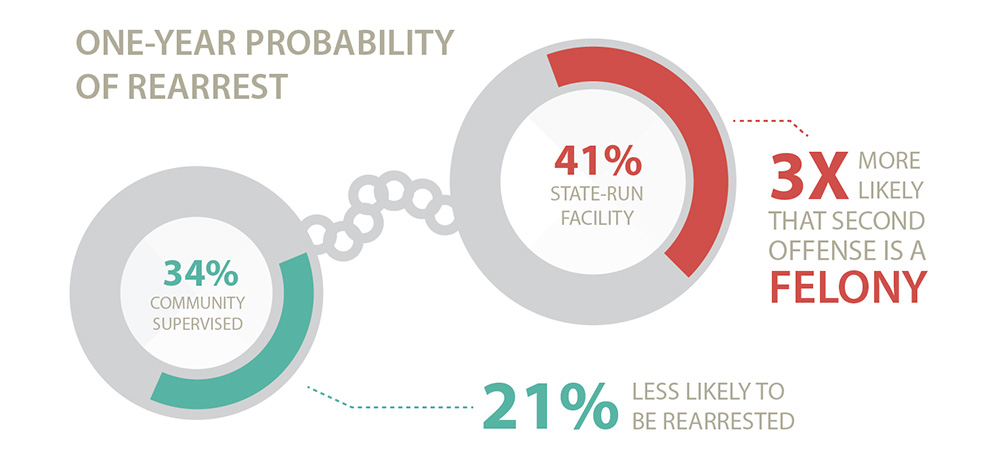

Juvenile criminal offenders in Texas who are placed under county supervision, close to home, are less likely to be rearrested than those placed in state-run correctional facilities, according to researchers at Texas A&M University.

The study “Closer to Home: An Analysis of the State and Local Impact of the Texas Juvenile Justice Reforms” was conducted by Miner Marchbanks III and Austin Clemens of the Public Policy Research Institute (PPRI) at Texas A&M, and colleagues at the Council of State Governments Justice Center, at the request of Texas state leaders in order to examine the effectiveness of 2007-2011 reforms made to the state’s juvenile justice system.

The reforms came in response to 2007 revelations of abuse in state-run secure juvenile correctional facilities. That same year, lawmakers prohibited youth who committed misdemeanors from confinement in secure facilities and lowered the age of the states’ jurisdiction over youth from 21 to 19, dramatically reducing the number of youth in confinement. Policymakers later established a grant program that gave financial incentives to counties to decrease the rate of confinement.

The researchers say the reforms resulted in a decrease of the average daily juvenile population in secure confinement — from 3,000-3,500 to about 1,000. “The decrease in population allowed for the closing of many facilities, saving the state millions of dollars,” says Marchbanks, an associate research scientist who specializes in criminal justice and education policy.

But most notable, say the researchers, is the finding that when juvenile offenders aren’t confined to secure facilities, and are instead under community supervision — such as juvenile probation, drug treatment programs, counseling or “boot camps” — recidivism rates decline.

According to the study, youth incarcerated in state-run facilities are 21 percent more likely to be rearrested, and they are three times more likely to have committed a felony if they are rearrested.

“One would think that if you take away this major punishment of confinement, crime is going to go up,” says Marchbanks, “but in fact, that’s not what happened. Recidivism doesn’t go up just from taking confinement away.”

Since there can be hundreds of community programs designed to help deter juvenile crime, the researchers categorized the programs as either skills-based (such as physical activities programs), treatment-based (such as counseling or drug treatment) or surveillance-based (such as probation requiring check-ins).

When analyzing the data, the researchers controlled for 41 variables including race, ethnicity and gender, gang affiliation, living situation, prior offenses, physical abuse and school outcomes.

The researchers say they suspect juveniles under county supervision are less likely to be rearrested due to a number of factors, one being continuing contact with family members.

“Many of these secure correctional facilities are located far away from home and due to time and financial constraints, family members might have been unable to visit very often,” notes Clemens, an assistant research scientist. “So this type of isolation from family could have had a negative effect.”

Marchbanks adds the researchers found a tremendous amount of randomness in courts deciding who went to state confinement and who went under county supervision. “When you are incarcerating juveniles with relatively minor offenses right alongside those who have committed more serious crimes, you may be exposing them to negative influences,” he says. “Then there’s the issue of perceived fairness; if your friend gets off with a treatment program but you’re sent to a secure facility 500 miles away, that has to have some sort of ‘the system is against me’ effect.”

He adds that keeping offenders in the community may also be more beneficial because local probation officers may know the children and the community better than a corrections officer hundreds of miles away at a state-run facility.

The researchers point to several standout Texas counties whose rates of recidivism since the reforms were enacted are notably low: El Paso, Dallas and Cameron.

And they add that Tarrant County, which fell into the “worse-than-expected category,” went about instituting reforms immediately upon this revelation. “They showed extraordinary leadership,” says Marchbanks. “Instead of ignoring the results or being defensive, they went straight to work for improvement.”