Floods carried pollution 100 miles off Texas coast, oceanographers say

A team of researchers that includes three Texas A&M University oceanographers has found that human pollution from floods in 2016 and Hurricane Harvey in 2017 made it all the way to the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary, located about 100 miles off the Texas coast.

Kathryn Shamberger, assistant professor at Texas A&M University’s Department of Oceanography, along with Texas A&M oceanographers Shawn Doyle and Jason Sylvan, and researchers from Rice University, University of Houston-Clear Lake, and Boston University have had their work published in the current issue of Frontiers in Marine Science.

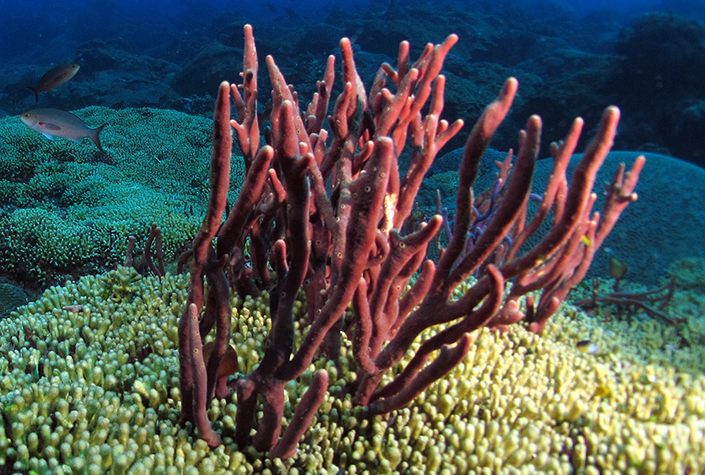

The team examined sponges in the Flower Garden Banks, a popular diving area known for its colorful coral reefs. It was designated as a national marine sanctuary in 1992 and now has 17 different reef systems.

The researchers found bacteria from human wastewater, including E. coli, in sponges at the Flower Garden Banks after flooding events in 2016. Hurricane Harvey in 2017 also carried contaminated water from the Texas coastline to the Flower Garden Banks. Researchers had previously believed the area to be far enough out in the Gulf that such pollution was not a concern.

Shamberger said the team was surprised to find bacteria typically associated with wastewater in coral reef sponges so far offshore.

“It has been known for decades that freshwater from land can reach these reefs and lower the salinity at the surface, but salinity changes that far offshore are small because freshwater mixes with seawater as it travels offshore,” she said. “Also, the Flower Garden Banks reefs are about 60 feet deep and low salinity water stays at the surface, so these reefs have been thought to be largely protected from land-based pollution.”

Doyle said the researchers used sponges living on the reefs as super-sensitive monitoring tools for water quality.

“Because they filter and concentrate bacteria from hundreds of gallons of seawater a day, looking at the sponges’ microbiomes (a collection of microorganisms that live on or inside an animal) allowed us to find signs of wastewater that were far too diluted to detect in the water column,” Doyle said. “Both flood periods that were sampled in this study showed bacteria associated with wastewater in the sponges, but we do not know how often floodwaters bring harmful bacteria all the way out to these coral reefs.”

Hurricane Harvey was the biggest rainfall event in U.S. history and dropped an estimated 13 trillion gallons of rain over southeast Texas in late August 2017.

The study was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Gulf Research Program of the National Academies of Sciences and Rice University.