Disarming bacteria? Phages may offer gentler remedies for infections

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIAID, part of the National Institutes of Health, NIH, has awarded $2.5 million in grants to support research on bacteriophage therapy, and Texas A&M AgriLife Research is among the grant recipients.

Bacteriophage therapy is an emerging field that many researchers think could yield novel ways to fight antimicrobial-resistant bacteria. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report from 2019 showed antibiotic-resistant pathogens cause more than 2.8 million infections and more than 35,000 deaths annually in the United States.

The new NIAID grants support research to address key knowledge gaps in the development of phages as preventive and therapeutic tools for bacterial infections. The AgriLife Research grant will provide two years of funding for research to help fill key knowledge gaps.

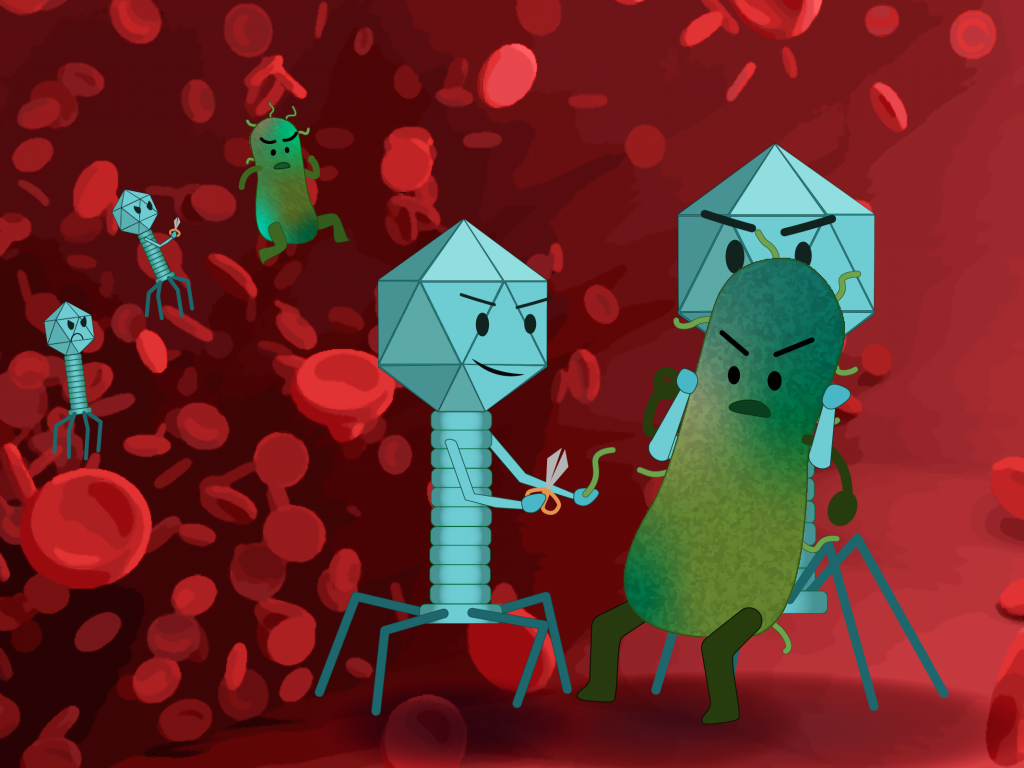

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that can kill or incapacitate specific kinds of bacteria while leaving other bacteria and human cells unharmed. Phages have been used to treat antibiotic-resistant infections, and researchers believe phages could be used in combination with antibiotics to help prevent bacteria from becoming drug resistant.

“If phages can be used to disarm bacteria, then this might be a gentler way to treat infections,” said Lanying Zeng, associate professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics at Texas A&M University. Zeng is one of the principal investigators for the NIH-funded AgriLife Research study. She is also a core faculty member of the Center for Phage Technology, part of AgriLife Research.

In the newly funded project, Zeng and co-principal investigator Junjie Zhang, also in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, will investigate how to reduce bacterial virulence by using phages to suppress pili—cylindrical structures on the surface of bacteria used for gene transfer and other functions.

Zeng said using phages to target pili could boost the action of existing antibiotics and possibly reduce the typical antibiotic dosage. She also noted that using these types of phages may give the immune system more time to fight off infection.

“And unlike traditional phage therapy, this will not kill the cell; it will just disarm it,” she said. “Killing the cell may cause a problem, because inside the cell there may be toxins that could be released into the host.”

The new research builds on a previous discovery made from an AgriLife Research-led study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in September 2020. That study showed certain phages cause pili to detach as the phages infect E. coli.