When deadly bacteria resist drugs, doctors turn to phage therapy

Scientists with the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences were among those providing the biochemical tools needed to help save a man’s life through a unique emergency intervention in 2016. Now those Center for Phage Technology scientists in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics have completed a study about that treatment as well as other opportunities for phage therapy.

Their study was published recently in the scientific journal Nature Communications.

The threat of antimicrobial resistance has become a worldwide concern, with the World Health Organization estimating at least 50 million people per year worldwide could die from it by 2050. Center for Phage Technology scientists believe phage therapeutics can be used to fight these resistant bacterial infections.

The premiere case involved phage center scientists working in collaboration with other scientists and physicians at University of California San Diego, UC San Diego School of Medicine, and the U.S. Navy Medical Research Center–Biological Defense Research Directorate. Together, they worked to identify phages and determine a treatment plan for Tom Patterson, a professor of psychiatry at the UC San Diego School of Medicine, who was infected by a deadly pathogen while vacationing in Egypt.

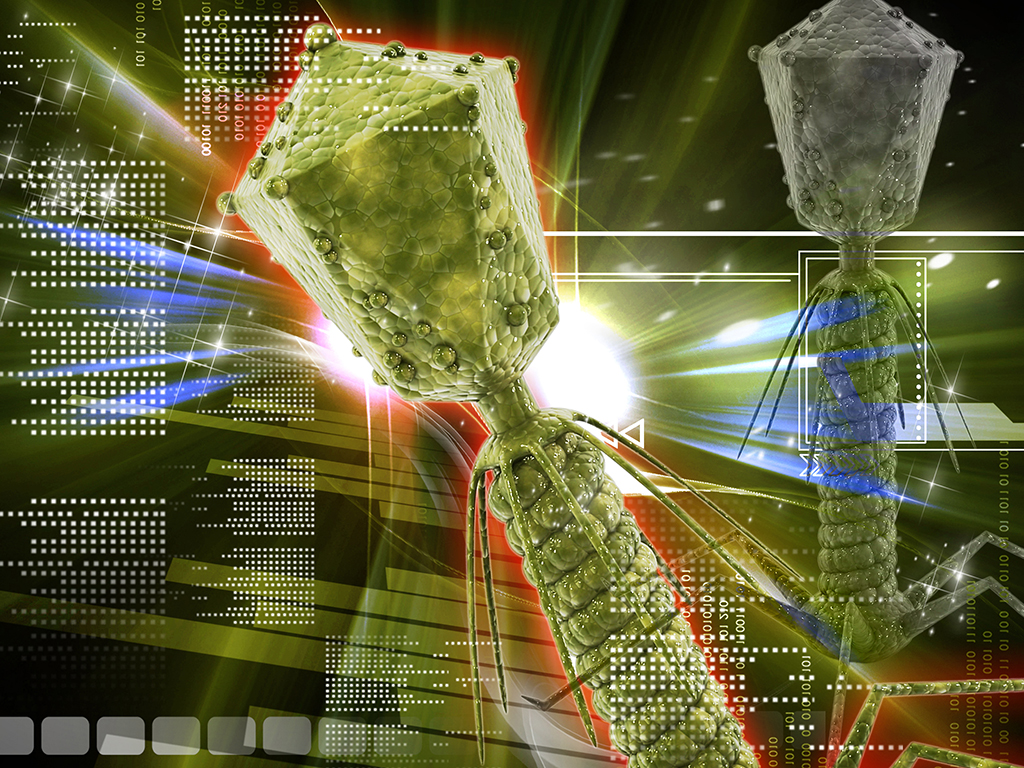

Bacteriophages, or phages, are viruses that can infect and kill bacteria without having a negative effect on human or animal cells. Phages can be used alone or in combination with antibiotics or other drugs to treat bacterial infections.

“Bacteriophage therapy is an emerging field that many researchers think could yield novel ways to fight antimicrobial-resistant bacteria,” said Mei Liu, program director at the Center for Phage Technology and a primary investigator for the study. “At the center, we are interested in the applications of phage therapeutics to fight multidrug-resistant bacterial infections.”

She said the center’s work is aided by the team’s deep knowledge of phage biology, particularly in the areas of phage lysis and phage genomics.

In 2015, while on vacation in Egypt during the Thanksgiving holiday, Patterson began to experience severe abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting. Local doctors diagnosed him with pancreatitis and treated him accordingly, but the treatments didn’t work and his condition worsened.

He was later transported to Germany, where doctors found fluid around his pancreas and took cultures from the fluid’s contents. The cultures showed he had been infected with a multidrug-resistant strain of Acinetobacter baumannii, an often-deadly pathogen found in hospital settings and in the Middle East. The same pathogen was also identified in many injured U.S. military members returning home after serving in that part of the world.

In Germany, Patterson was treated with a combination of antibiotics, and his condition improved to a degree where he could be airlifted to the intensive care unit at Thornton Hospital in the UC San Diego Health academic health system. There, however, the medical team discovered that the bacteria had become resistant to antibiotics.

A “compassionate use” exemption for phage therapy was requested by Robert “Chip” Schooley, the UC San Diego physician treating Patterson. He was given rapid approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, FDA, to proceed.

Shortly after the phage treatment began, Patterson awakened from a months-long coma. After a long recovery, his health improved greatly, and he was able to return to life as it was before the infection.