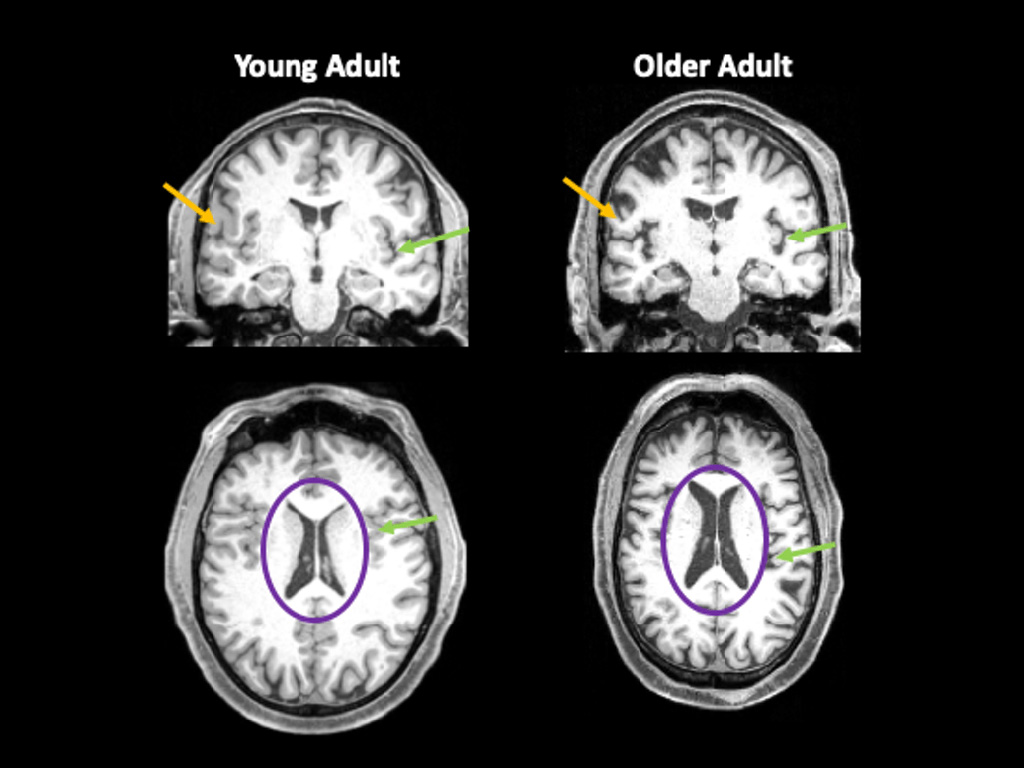

Long-term effects of COVID-19: Infection may decrease brain volume and alter neural pathways, according to two new studies

As reports began to spread this past spring of a United Kingdom-based study showing people who have had COVID-19 suffered more brain-volume loss than those who had never contracted the virus, Texas A&M University professor Jessica Bernard simultaneously was conducting her own research revealing differences in communication between regions of the brain in COVID-19-afflicted people.

In parallel, Bernard says two similar outcomes on two different continents could mean several things for the one in three Americans estimated to have been infected with COVID-19 since January 2020.

The U.K. study evaluated a large sample of individuals in what is known as a longitudinal study. Some individuals had other infections, such as pneumonia and flu, yet even with those respiratory illnesses as a comparison, COVID-19 showed significantly more longitudinal changes.

Bernard, an associate professor in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, and her team have also been conducting a longitudinal study since the beginning of 2020. Though the results of the study are unpublished, they were presented at an American Psychological Association Meeting.

“In my group, we’ve been doing an ongoing longitudinal study that, by sheer coincidence, happened to start around when the pandemic hit,” Bernard noted. “We had to shut down for a while, as you know, right in March [of 2020]. In that sample, we were already following people. We’ve been following people for over two years. We have started asking people if they have had COVID-19. We’re trying to see whether or not we can follow up and replicate some of these differences seen in Douaud’s study in our own sample because we’re tracking them over time.”

Bernard and her team are hoping their study adds to the information already discovered about COVID-19 and its effects on the brain, including a recent study that seniors who had COVID-19 had a substantially higher risk of being diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease within a year.

“We don’t see in our sample any differences in their behaviors,” Bernard said. “We looked at some motor tasks and cognitive tasks measuring how quickly people process and organize information. There are no differences there thus far. Then, when we looked at brain networks, though, we saw some differences in how the brain is communicating with different regions and how these different regions are talking to one another in individuals that have had COVID relative to those that have not. The parts of the brain that seem to be impacted in our unpublished study are similar to the parts of the brain that show volume differences in the study by Douaud and their colleagues.”