Flipping the switch: Light-activated cells can focus on attacking tumors while reducing side effects for cancer patients

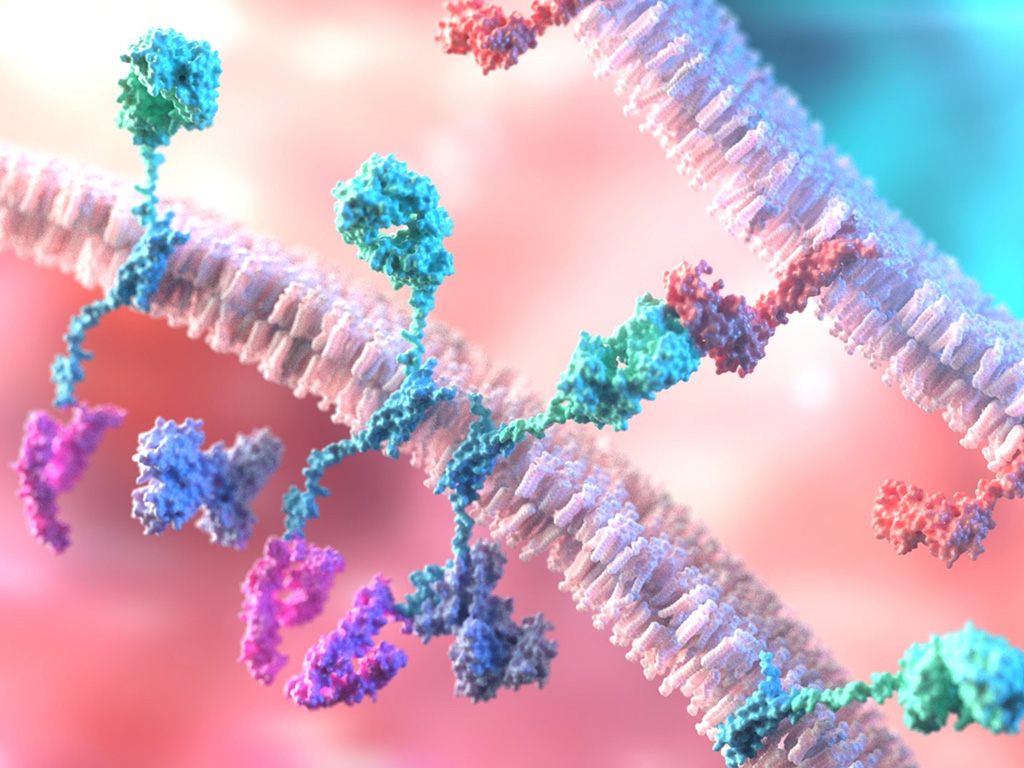

For patients with certain types of blood cancer, a type of cancer treatment called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy can be a “miracle” cure, keeping them cancer-free for many years. These “living” drugs are a type of immunotherapy that use the patient’s own immune system to fight the cancer.

In 2017, a drug called Kymriah was among the first CAR T-cell therapies to receive approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma. Following that, the FDA approved more similar therapies for the treatment of various types of blood cancer. Despite the miraculous efficacy, a portion of cancer patients receiving CAR T-cell therapy will experience serious side effects, which often arise because of the lack of controlled activation over the anti-tumor immune response triggered by the engineered T-cells.

To address this challenge, researchers at the Texas A&M Health Institute of Biosciences and Technology (IBT) and the Department of Translational Medical Sciences at the Texas A&M University School of Medicine developed one type of intelligent T-cells, termed “light-switchable CAR T-cells” (or LiCAR-T), that can rapidly respond to light to switch on their tumor-killing capabilities. Yubin Zhou, professor and Presidential Impact Fellow at the Center for Translational Cancer Research at the Institute of Biosciences and Technology, and Yun Nancy Huang, associate professor at the Center for Epigenetics and Disease Prevention, led the study developing LiCAR-T cell immunotherapy for cancer treatment. Their study was published in the journal Nature Nanotechnology.

“CAR T-cell immunotherapy has shown a high potential for tumor eradication, and the field has seen encouraging complete remission instances like Emily Whitehead and Bill Ludwig,” Zhou said. “However, CAR T-cell therapy still has some notable safety challenges because of devastating adverse effects associated with poor control over its anti-tumor activity.”

Some of these adverse side effects are cytokine release syndrome, immune effector cell-associated neurotoxicity syndrome and the depletion of normal B cells. “CAR T-cell therapy may cause cytokine storm due to the rapid activation of T-cells within a short time window after recognizing tumor cells. In some cases, this might send patients into the intensive care unit,” Zhou said.

FDA-approved CAR T-cell therapies are mostly designed to target the CD19 antigen, which is abundantly expressed on the surface of cancer cells but is also present on normal B cells. Therefore, they lack the ability to discriminate between normal CD19-positive cells and cancerous CD19-positive cells, which could lead to a common side effect known as B-cell aplasia (depletion of leukocytes in the blood). These side effects are manifested in multiple clinical symptoms, including fever, low blood pressure, neurological changes and multi-organ failure, potentially leading to death.

“To address this issue, we came up with the idea of using light as a non-invasive means of controlling the activation of therapeutic immune cells. By doing so, we can selectively switch on tumor-killing immune cells within the tumor sites, but not elsewhere, to substantially reduce side effects. More impressively, the LiCAR-T platform allows us to fine-tune anti-tumor immune response by simply playing with the light pulse and intensity,” said Huang, a Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) scholar in cancer research.